With more than 4,000 companies in Connecticut forming the supply chain for aerospace and industrial giants like Pratt & Whitney, Sikorsky and General Dynamics Electric Boat, manufacturing plays a critical role in the state’s economy and future.

In 2019, according to the National Association of Manufacturers, the sector accounted for $29.6 billion in economic output in the state, while employing nearly 10% of Connecticut’s workforce.

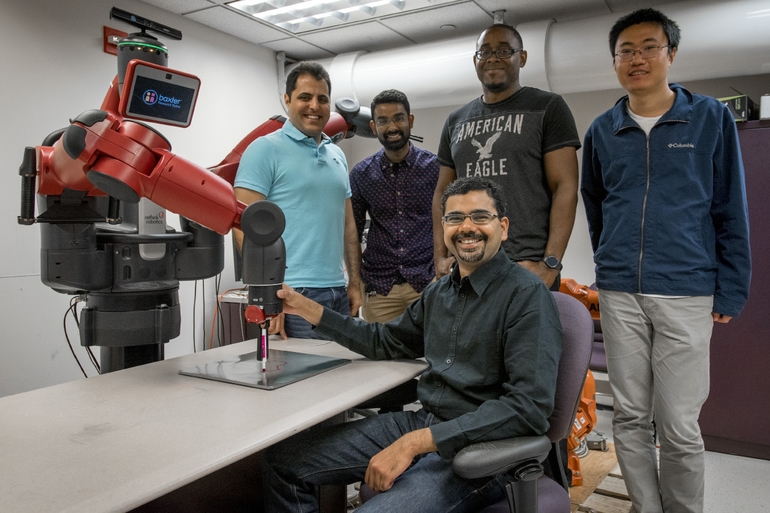

As manufacturers across the state look to increase production and competitiveness through automation and cognitive computer and artificial intelligence — a sector evolution known as the fourth industrial revolution or Industry 4.0 — the state’s flagship university, UConn, is trying to help create a pipeline of talent with a new robotics major starting in the fall of 2022.

John Chandy, head of UConn’s electrical and computer engineering department, which will oversee the robotics coursework, says the program will incorporate the disciplines of electrical engineering, computer engineering, mechanical engineering and computer science.

UConn is one of only two U.S. research-active universities to offer a robotics major. While the school has a history of robotics research among engineering faculty, which has transferred to companies or fueled startups, Chandy says one of the goals is to get new robotics majors thinking about business opportunities.

“Even at the freshman level, we need to change the mindset,” Chandy said. “Many [engineering] students come in thinking about [getting] a stable job at a big company [after graduation], but we want them to think about entrepreneurship as an option.”

And the robotics job market is heating up. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 9% job-market growth for robotics engineers between 2016 through 2026 with an average salary of $81,000. The global robotics market is projected to grow 26% annually to just shy of $210 billion by 2025, according to Statista, a market research firm.

Pandemic boosts automation

Those numbers don’t surprise Ron Angelo.

As president and CEO of the Connecticut Center for Advanced Technology (CCAT), Angelo’s organization works with nearly three dozen global industrial companies and thousands of supply chain manufacturers across the state.

“We listen and get feedback from [employers] about what’s most important [to them] and that is advanced design automation, robotics for inspection and quality control, and additive manufacturing,” Angelo said, noting CCAT recently modernized its three East Hartford-based training facilities to align with manufacturers’ growing technology needs.

And COVID has only quickened the drive for automation. National data from Westmonroe, a digital technology company, found that manufacturers digitized many activities 20 to 25 times faster last year because of the pandemic, prompted by the need to move at faster speeds as they adjusted to constraints with their workforce, suppliers and customers.

Additionally, the report noted that 82% of manufacturers surveyed have implemented, piloted or are considering Industry 4.0 technology.

As component parts for robots — like cameras, sensors, lasers, and scanners — become less expensive, the overall cost of robotic automation has dropped, too, says Jim Mail, regional sales manager for ABB Robotics, one of the world’s leading robotics and machine automation suppliers that sells to Connecticut-based companies.

That’s enabled small and mid-sized businesses to incorporate more automated technology.

“As costs have gone down, the return on investment has gone up,” Mail said.

One of the fastest growth areas in robotics is in distribution logistics and warehouse automation. Amazon, for example, uses robots to move massive amounts of inventory at its warehouses, including in Connecticut.

Sweedish lockmaker ASSA ABLOY uses various robotic and automated technologies at its Berlin manufacturing plant on Episcopal Road. That includes cobots, or collaborative robots that operate alongside workers to perform actions that don’t require the skill of a human.

For example, a cobot equipped with grippers picks up a mortise lock body from another fabrication process and sends it to a line worker who performs late-stage assembly or lock customization.

Today, Mail says, machines are being designed with artificial intelligence and machine-learning capabilities, so they can not only pick up an object, for example, but distinguish among various factors, like different bar codes.

“There are vision systems [with some robots] that help [the machine] make decision-tree type decisions,” he said.

Upskilling workers

Another advantage of automation, Mail says, is it allows companies to use machines to handle mundane, repeatable work and upskill employees to perform higher-level tasks.

Such upskilling is a major focus and concern in the manufacturing industry, especially in Connecticut, which continues to face a workforce shortage. There are thousands of available jobs in the industry today.

The Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Institute, of which UConn is a member, notes the lack of continual re-skilling as one of the sector’s top challenges, along with a U.S. educational system that is insufficient for advanced manufacturing careers.

CCAT’s Angelo understands those challenges. He says programs like the First Robotics Competition, a nationwide robotics program at the high-school level, have been great, but more needs to be done at the college level, which is why he is encouraged by UConn introducing its robotics major.

“Jobs that become available because of automation will grow exponentially in the manufacturing trade,” Angelo said. “We’ll need programmers and coders [in manufacturing], the type of skills that were traditionally attractive to the insurance and financial services and healthcare industries.”

Chandy said he hopes UConn’s newest major will help create and grow a robotics ecosystem of startups in Connecticut over time to support in-state companies.

For now, he and his colleagues in the engineering department are preparing for the first class of robotics majors next fall. He expects the program might attract 30 to 40 students in its inaugural year but is hopeful that number will swell to 300 students in the years ahead.