To train the workforce, manufacturing companies have essentially created their own schools

Last school year, about 15 students from Manchester West High School received instruction from over a dozen different teachers, and visited a local manufacturing company on multiple days to tour the facility and shadow different operators, all for a single class.

It was Velcro University’s inaugural year, and the partnership between Velcro Cos. and West High proved successful, according to Velcro corporate affairs business partner Mark Elliot. While students had the opportunity to learn about Velcro, the course curriculum was designed to prepare students to navigate any workplace environment.

“The program was designed to prepare the learner to enter the workforce,” Elliot said. “We don’t really go in to teach them Velcro-Companies-related coursework.”

Hitchiner Manufacturing Co.

594 Elm Street, Milford

Founded: 1946

Employees: About 750 in New Hampshire

School credit program: Manufacturing Exploration and Externship

Students per term: 12 students per semester

Program focus: Engineering basics and manufacturing experience

Spraying Systems Co.

243 Daniel Webster Highway, Merrimack

Founded: 1937

Employees: About 50 in New Hampshire

School credit program: Manufacturing Exploration and Externship

Students per term: 12 students

Program focus: Engineering basics and manufacturing experience

While not every student trained through the program will end up working for Velcro, the arrangement is a win-win for the company and school district, Elliot said. It prepares the next generation of workers, and exposes them to a modern-day manufacturing workspace, dispelling common myths about dirty and unsafe conditions in the process. And the school benefits from the investment of the company’s time and money to produce more well-rounded students.

“Workforce development is one of our most significant concerns. We need to have the next generation of operators so that we can continue to manufacture,” Elliot said.

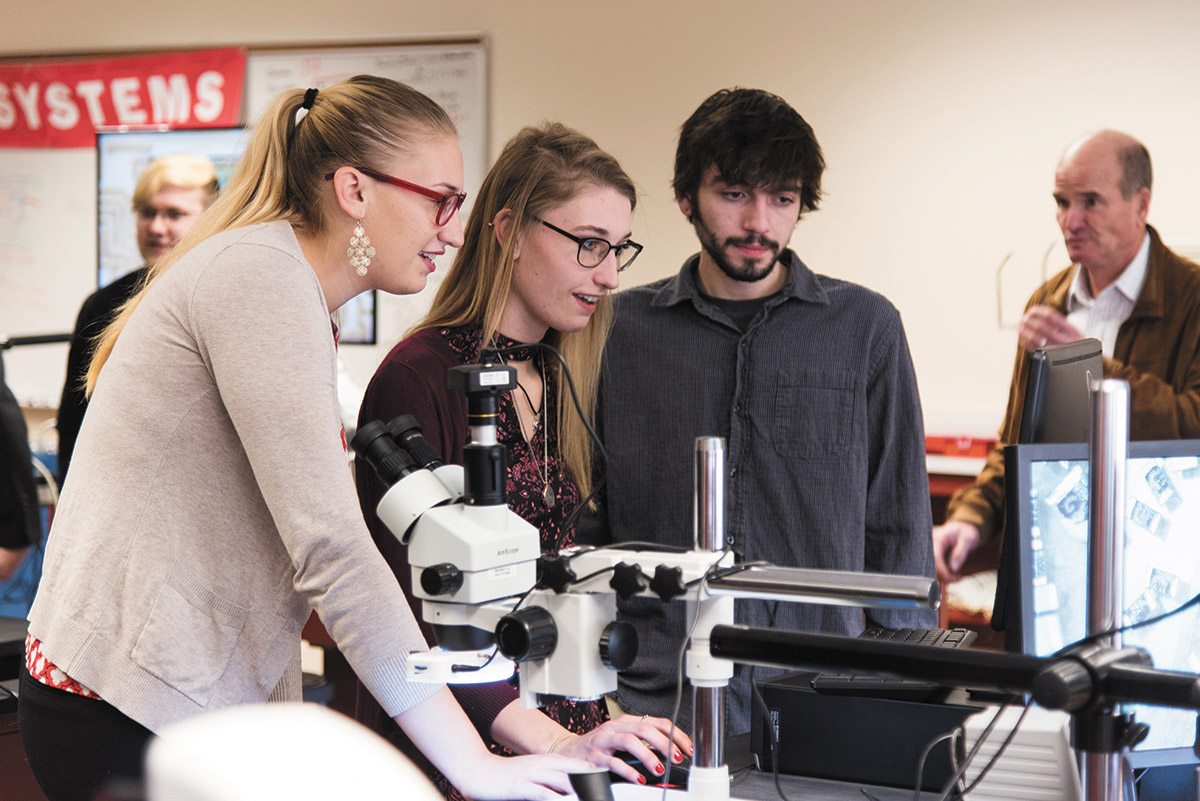

Students participate at the Micro-electronics Boot Camp program offered by Nashua manufacturer BAE Systems.

These kinds of partnerships are cropping up everywhere in New Hampshire, for high school students or adult students of all ages turning to community college because they want to change careers.

In many cases, they are facilitated by the New Hampshire Manufacturing Extension Partnership’s Partnership Sectors Initiative, but in many other cases, they’re being created ad hoc by the local partners themselves.

The reason for the growing ubiquity of these partnerships, in part, is a now universally recognized need to close the gap between companies who sorely need workers and schools that ready them for the workforce.

BAE Systems

65 Spit Brook Road, Nashua

Founded: 1999

Employees: 6,000 in New Hampshire

School credit program: Micro-electronics Boot Camp

Students per term: About 16 people per 10-week cohort, 4 cohorts per year

Total students educated: About 130

Program focus: Micro-electronics assembly

Jacqueline Guillette, a former superintendent for schools in Claremont, Unity and Cornish, and current education consultant, remembers the days before people started talking about closing the so-called skill’s gap and emphasizing the need for more science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) education.

Today, STEM training and manufacturing partnerships with schools is the buzzword, Guillette said, but eight years ago, people only started talking about it.

As superintendent, she ushered the district into a deal with Whelan Engineering Co. in Charlestown to create one of the first such partnerships, after working closely with the company’s CEO on the Governor’s Advanced Manufacturing Education Advisory Council starting in 2008.

Claremont students have been going to Whelan for an hour of learning five days a week for the past eight years. This year, Charlestown students have asked to join in, Guillette said.

“Whelan was probably the first to lean in on this kind of thinking eight years ago,” Guillette said.

Over the years, as the thinking evolved, the state has made steps to replicate and expand these kinds of partnerships.

For example, the Business and Industry Association teamed up with the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation to create a position called a workforce accelerator, currently held by Sara Colson. And the state Department of Education hired Dean Graziano, the extended learning opportunity coordinator for the Rochester School District, to create the New Hampshire Career Academy.

The academy operates as an embedded charter school inside the state’s community colleges, providing high schoolers with up to 30 college credits and an Advanced Composite Manufacturing certificate.

Companies like Albany/Safran in Rochester and Timberland Shoes in Stratham are partners.

“Knowing that New Hampshire is not a top-down state, it’s a local control state, really good ideas tend to come from individuals and individual organizations,” Guillette said.

While planning for programs like these started years ago, Guillette said some are just now coming to fruition. The reason for that is that it often requires a lot of groundwork to get the programs going, such as authorizing district policies, budgeting programs and finding the people to put them together.

The Newport School District, for example, created a graduation requirement for substantive career education and experience six years ago. Now, this year’s sophomores will be the first cohort to graduate with that program in place, Guillette said.

Paige McNamara from Manchester West High School participated in the Velcro University program. Photo by Matthew Wright

Velcro University

Manchester’s partnership with Velcro is on the cutting edge of this movement. In its first year, there were about six to seven students participating per semester. But in future years, it should have room for 12 to 14 per semester.

The idea for the program came out of discussions between the company’s president of North America and chief commercial officer, Dick Foreman and Manchester Mayor Joyce Craig about 14 to 15 months ago, according to Elliot.

Velcro Cos.

95 Sundial Ave, Manchester

Founded: 1952

Employees: About 750 in New Hampshire

School credit program: Velcro University

Students per term: 12 to 14 students per semester

Total students educated: 15

Program focus: General workforce preparation

The coursework is divided into different topic areas, with different employees from Velcro stepping in to teach them. The first days begin with courses on employee benefits, codes of conduct and emotional intelligence, which are taught by Velcro human resource executives.

Part of the idea behind having different roles stepping in for the instruction, Elliot said, is to showcase positions students may not even know exist.

“Then they dig into more of the manufacturing side of the business,” Elliot said.

Students learn about structured problem solving, performance metrics, safety and manufacturing processes. They also spend two full days shadowing operators and checking out the different Velcro facilities.

At the end of the course, students do presentations before the Velcro instructors, which demonstrates what they’ve learned but also gives them a dry run at another corporate skill. Elliot said the courses are very discussion and dialogue oriented, with instructors treating students like adult colleagues.

“We got tremendous response from the students,” Elliot said. “The relationship that they develop over that five or six hours is amazing.”

Elliot said Velcro invested its own resources renovating a classroom at West High for the program, designing it to look like a modern office space with a big screen TV wired into a remote video conferencing network, and providing 14 to 16 of its own employees to help teach.

They worked closely with Principal Rick Dichard on creating the curriculum.

Micro-electronics Boot Camp

While the Manchester program is still new, some companies have gotten a head start trying to create a direct pipeline of workers through the available education systems.

Butch Lock, the manufacturing director at BAE Systems in Nashua, said he worked with Nashua Community College about 3.5 years ago to create a program taught at the school called Micro-electronics Boot Camp.

For 10 weeks, a cohort of about 16 students, usually in their mid-20s to mid-50s, studies how to handle micro-chip assemblies and connect gold wires a third the width of human hair.

“The job, the curriculum, the execution of the instruction, that’s all done by the college and people that are employed at the college,” Locke said.

The company and school crafted the curriculum hand-in-hand, he said.

“Nashua Community College was the one who said, ‘What do you need? We’ll make it happen.’” Locke said.

At the end of the program, students are promised a tour and job interview with BAE Systems.

There are four cohorts every year, from January to early December. Out of the 130 who have graduated from the program to date, 103 have gotten jobs at BAE, Locke said.

“This wasn’t going to be a 100% solution for our need, but it definitely contributed,” Locke said.

Locke said he sits on the (Sectors Partnership Initiative) SPI committee and other members from around the state are asking him how they can replicate this program.

Alene Candles’ Manufacturing Exploration and Externship program will host about a dozen students per term.

Manufacturing Exploration and Externship

Meanwhile, other programs geared toward creating a workforce pipeline from high school to manufacturers are poised to launch this year. In Milford, the engineering program at Milford High School is partnering with three manufacturing companies in the area to divide up the in-class coursework with hands-on experience as actual paid employees.

Spraying Systems Co.

243 Daniel Webster Highway, Merrimack

Founded: 1937

Employees: About 50 in New Hampshire

School credit program: Manufacturing Exploration and Externship

Students per term: 12 students

Program focus: Engineering basics and manufacturing experience

Milford High engineering teacher Frank Xydias said the school started planning the program last October with the help fo Hitchiner Manufacturing Co. This fall, the first cohort of seniors and juniors will be provided paid externships (for $12 per hour) at three companies; Hitchiner in Milford, Alene Candles in Milford and Spraying Systems Co. in Merrimack.

While the students spend time rotating through the three companies, they learn their manufacturing processes, from basic measuring tools to robotics automation to CNC set up and operation. Students also learn about the interview process, building resumes and safety equipment.

“Each student will be at each company for about five weeks,” Xydias said.

Students spend three days a week in the classroom, and two days a week at the companies working up to three hours each day. The coursework is curated from existing engineering curriculum units provided by Tooling U, a program of the Society of Manufacturing Engineering.

For participating in the course, students each get seven college credits through the running start program.

After the semester ends, students are offered opportunities to continue working for a company of their choice full-time.

The companies have invested quite a bit of money in the program, Xydias said.

While the running start credits are currently covered by the state, the companies have committed to covering the cost — an estimated $300 per pupil — should state law change that.

And Xydias said the program is being watched closely by top politicians. Sens. Jeanne Shaheen, Maggie Hassan and Rep. Annie Kuster each have representatives on the planning committee, he said.

“There’s so much good stuff going on,” education consultant Jacquelline Guillette said.

While the state has made great leaps forward in creating opportunities for students to learn about the local job opportunities in manufacturing, and for companies to dip into a labor resource they have a hand in preparing, Guillette said there’s still a lot more work to be done. ◾